|

It Starts

with the Grain�.

| Of

course, grist mills grind of variety of grains, such as

wheat, rye and corn. But in Rhode Island, particularly at

Gray's Mill, native-grown corn, particularly Narragansett

White Flint Corn, was the most common "grist for the mill."

The corn is husked, then dried for six months. It is then

shelled, and packed for grinding. |

|

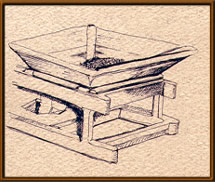

Into

the Hopper�

|

The

dried, shelled corn is then poured out of the bag, and into

the hopper. The hopper, of course, is the receptacle above

the grinding stone. A vertical rod, called the "damsel,"

is used to shake the kernels downward, through the "shoe"

and onto the millstone. The hopper releases an average of

three bushels of corn an hour for grinding. |

A Word

About the Millstones�

| The

two granite millstones at Gray's Mill are 15 inches thick,

and weigh a total of 1 ½ tons. An enormous tonnage,

considering that they were imported from France. Originally,

one stone was used for food, and the other for animal feed.

The

grinding surface of these "runner" stones, or

top stones, is concave and carved in spoke patterns. The

runner stone sits atop another "bed stone" or

"nether stone," which is also carved. As the

top stone rotates, the grain first gets cracks in the

middle of the two stones, then is pushed to the outside

by the spoke-like pattern. The finest grinding occurs

along the perimeter.

When

the millstones need to be cleaned, sharpened or repaired,

the runner stone is lifted with a Stone Crane, using a

pulley.

|

|

Turning

the Stones�

|

Traditionally,

the millstone rotates by waterpower. At Gray's Mill, a Sluice

Gate was used to start and stop the flow of water from the

mill pond across the street. The Sluice Gate is opened by

turning the Sluice Gate Wheel, which starts the flow of

water, causing the water wheel to turn, thus providing power

to grind the grain.

Eventually,

as water levels in the mill pond became unreliable, drying

out during much of the year, water power at Gray's Mill

was supplemented with a 1946 Dodge truck engine from an

old Cain's mayonnaise truck. By 1960, the mill was powered

entirely by this engine.

|

Separating

the Chaff �

|

As

the ground corn falls from the grain spout, it is filtered

through a mesh screen that sifts out the coarser pieces

of the corn's bran, or outer layers.

These

coarse remains are placed in the "Chaff Bin"

and used for animal feed by local farmers.

|

On to the

Market �

| Freshly

ground sacks of corn are then hauled into the bagging room,

where it is weighed on a scale and hand-bagged using a funnel.

Since traditionally milled corn contains none of the preservatives

found in store bought grains, it must be kept refrigerated

to preserve freshness. |

|

|

|